27th May 2022

The Merri Creek School Story – a glimmer of compassion in the sad story of Melbourne’s beginnings

As we reflect on the importance of National Reconciliation Week, Baptcare’s Head of Spiritual Care Geoff Wraight shares the story of an early Baptist Church initiative in Melbourne.

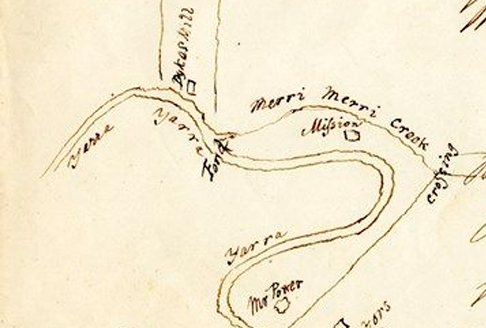

In 1835 on the banks of the Merri Creek somewhere near what is now called North Fitzroy John Batman’s famous sham ‘treaty’ was ‘signed’ with five or more Aboriginal clan heads. These proud Kulin elders probably believed they were participating in a tanderrum ritual – a ceremony in which a ritual exchange of gifts granted permission for temporary access to land.

Batman was unaware or chose to ignore the fact that Aboriginal land with its sacred responsibilities and its source of livelihood, could not be bought or sold. His attempt on behalf of a Tasmanian pastoral company to acquire 600,000 acres of land was disavowed by the NSW Government in September of that same year but this was the dubious beginning of the settlement of Melbourne town.1

The impact of European presence in what was a key meeting place for the member clans of the Kulin people (particularly the Woiworung and Bunurong), was sudden and dramatic. The settlers grew in number and spread out with their sheep and cattle and soon more and more areas became off-limits for the Koories.2

The sad story of the forcing out of the Koorie peoples from the Melbourne area was punctuated by acts of compassion from some of the early settlers not least the people of Collins Street Baptist Church which had its beginnings in 1839.

In 1845 some members of the Collins Street church established a school for Koorie children near the Merri Creek encampment. At its peak, there were 26 aboriginal children attending the school learning spelling, reading and singing. Though in hindsight this may seem an intrusion on culture, at the time this attempt to treat the Indigenous peoples of Melbourne as capable of learning and education was radical. So radical in fact that it fuelled debate about whether the Aboriginal people were capable of ‘civilisation’.3

By the end of 1847, the Wurundjeri clan had left Merri Creek in the face of increasing persecution and moved from Yarra bend taking their children with them.

The school continued with a change of teacher and a smaller number of pupils, mainly from outside of the Melbourne area. At the end of 1847, there were six acres of vegetables under cultivation and many of the children could read and were learning to write. In 1849, an extraordinary cantilever bridge was constructed over the creek by the children and teacher, but it was swept away in a flood in 1850.

With the bridge gone, gardens destroyed and the press fanning public criticism of the school as a waste of money, it was officially closed in 1851.

While this a sad story, it is also one that shows that at the heart of the local engagement of those earliest Melbourne Baptist people was some sense of inclusion and dignity that they felt toward the original and dispossessed Kulin peoples who were forcibly displaced from their home of thousands of years.

1 Mayer Eidelson, The Melbourne Dreaming: A Guide to the Aboriginal Places of Melbourne, Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 1997, p. 28

2 Gary Presland, Aboriginal Melbourne: The Lost Land of the Kulin People, Harriland Press 2001, p104-105.

3 See “The Merri Creek ‘experiment’” in Ken Manley, From Woolloomooloo to Eternity: A History of Australian Baptists, Paternoster, 2006. pp43-44

Visit Baptcare for more stories and the National Reconciliation Week website to learn more.